The genre of historical painting is an interesting one. Its defining characteristic is that the paintings are a snapshot of a historic moment, a recounting of a story.

Liberty Leading the People (1830)

It seems that somehow this once prolific genre has mostly been replaced by journalistic photography, which performs an analogous but slightly different task. The limitation with photography for this purpose is that while it’s easier to convey a moment, it’s more difficult to expound on the context and narrative surrounding it. With painting though, one has greater freedom to tell the story the way they want to tell it, and decide to choose elements of the story they deem relevant and irrelevant. In that sense, historical painting is not unlike a textual retelling.

Inevitably, with the ability to freely guide narrative in historic events comes political commentary. The Polish painter Jan Matejko, considered to be one of Poland’s best, is a master of this form of commentary.

During the 19th century Polish lands were occupied by Russia, Prussia and Austria, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceased to exist. Russia and Austria engaged in explicit anti-Polish activity, including banning the language in schools, in an effort to stamp out nationalistic disagreement. A fervent patriot, Matejko wanted to aid his country in the January Uprising of 1863 against Russia, but was not healthy enough to do so. Instead, he donated most of his savings, carried arms, and painted pictures.

While independent Poland didn’t exist during the 18th century, Matejko’s paintings won awards in Europe, helped spread awareness of the political events that took place and reminded the world of Poland’s national cause.

One of my favourite paintings of all time is Matejko’s rendition of Stanczyk (which I’ll talk more about in a bit). The court jester to three Polish kings in the 15th and 16th centuries, Stanczyk was a controversial figure. While he was indeed an entertainer, he was also known and revered by his contemporaries during the Renaissance as a great political thinker who used his humor and wit to make politicians aware of their follies.

The most famous Stanczyk anecdote is about an incident that happened during a hunt:

"In 1533 King Sigismund the Old had a huge bear brought for him from Lithuania. The bear was released in the forest of Niepolomice near Kraków so that the king could hunt it. During the hunt, the animal charged at the king, the queen and their courtiers which caused panic and mayhem. Queen Bona fell from her horse which resulted in her miscarriage. Later, the king criticized Stanczyk for having run away instead of attacking the bear. The jester is said to have replied that ‘it is a greater folly to let out a bear that was already in a cage’. This remark is often interpreted as an allusion to the king’s policy toward Prussia which was defeated by Poland but not fully incorporated into the Crown." — Wikipedia, "Stanczyk"

Prussian Homage (1881)

Sure enough, in a painting Matejko made of the Prussian Homage, an event where the duke of Prussia swore allegiance to the king of Poland, Stanczyk can be seen sitting below the king with a skeptical expression. The duke of Prussia is kneeling on both knees, which appears to be to be a symbol of his insincerity and disloyalty, since dukes only kneeled with both knees in front of God.

But this is separate from Matejko’s original rendition of Stanczyk, which is perhaps his most famous painting. Pause a second and click to take a closer look:

Here, Stanczyk sits alone in deep contemplation, perhaps worry. He wears a fool’s outfit, complete with bells and pointy hat, but is he really such a fool? Behind him, in the other room, everyone else is partaking in a lively celebration but he has no appetite for it. His marotte (a jester’s scepter with a miniature head on it) is tossed on the ground. On the table lies a letter with an official seal. It was presumably crumpled up by someone else, since Stanczyk seems concerned about it.

The text on the letter mentions Smolensk, a reference to the loss of Smolensk to the Russians in 1514, which is what Stanczyk is worried about, but no one else seems to grasp the importance of. Smolensk is quite close to Moscow, the capital of Russia. At its height, the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth was a significant power that could hold such lands. Everyone else doesn’t doubt the continuation of this power, as they celebrate the victorious Battle of Orsha that happened around the same time.

The loss of Smolensk, however, marks a change in the tides of power. There is a comet in the sky that can be seen through the window. This is an omen of things to come. An entertainer with dwarfism plays a musical instrument: Dwarfism at the time would symbolize people of lower standing and caliber, suggesting the character of the kind of rulers who would celebrate while danger is ahead.

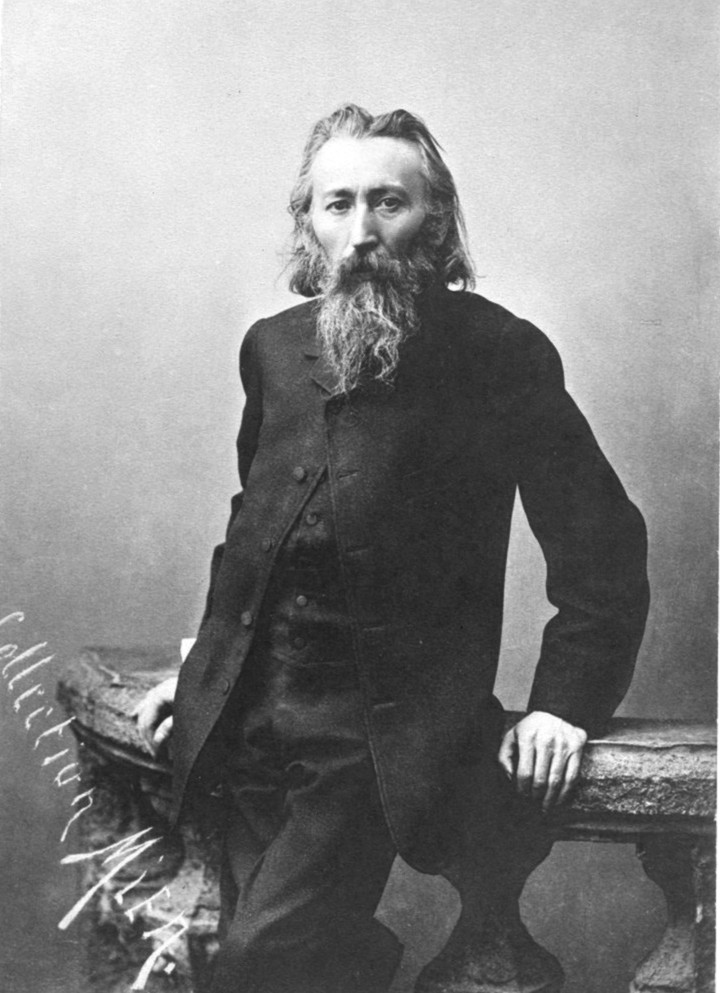

Jan Matejko by Jules Mien (before 1883)

Finally, Stanczyk’s facial features match Matejko’s own. This whole picture is an allusion to the emotions Matejko had towards the fate of his country while it was under invasion.

The most appealing part of Stanczyk is that he defies the stereotypes of the philosopher, the politician and the patriot, while being all three: Philosophers are supposed to be formal and sober, while Stanczyk is witty and jovial. Kings and other politicians dress and carry themselves with gravitas, and expect to be treated accordingly, while Stanczyk wears a self-deprecating fool’s costume with bells. The avowed patriots are at the ball celebrating Poland’s victory, while Stanczyk worries alone in a room for its future.

Thanks

Many thanks to Mikolaj Machowski and The National Museum in Warsaw for spending the effort to answer my e-mail promptly and for making public a high quality digitized version in which the aforementioned details can be observed.